[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

Just When it Was Starting to Feel Real by Matthew Murray

-

Official screen versions of Broadway shows generally fall into one of three distinct categories. In order of decreasing rarity: the honest-to-goodness adaptation (transform a play into a film, such as with last year's semi-acclaimed Doubt); the documentary (make a film about making a play, as in the case of Every Little Step); and the preservation (actually film a play, onstage and with an audience, the kind of thing you might see on Live From Lincoln Center or, even more infrequently, for sale like Victor/Victoria).

Official screen versions of Broadway shows generally fall into one of three distinct categories. In order of decreasing rarity: the honest-to-goodness adaptation (transform a play into a film, such as with last year's semi-acclaimed Doubt); the documentary (make a film about making a play, as in the case of Every Little Step); and the preservation (actually film a play, onstage and with an audience, the kind of thing you might see on Live From Lincoln Center or, even more infrequently, for sale like Victor/Victoria).What you never see, however, is all three occurring simultaneously within the same work. That Spike Lee's new film of Passing Strange, a record of the enthusiastic 165th—and final—Broadway performance of the Stew–Heidi Rodewald musical on July 20, 2008, tries just that explains why it's both an intoxicating record of the show and yet considerably less than the sum of its parts.

Lee, who's best known for directing bracingly gritty urban exposés like Do the Right the Thing, Malcolm X, and 25th Hour, would seem to be ideal for guiding this show to the screen. Following a young Los Angeles man who searches for personal and musical fulfillment in Amsterdam and Berlin before discovering his truest voice was always at home, Passing Strange spends almost all its time meditating on the nature of racial identity, personal identification, and the yawning chasms that so frequently exist between the two. The Youth (played by the scintillating Daniel Breaker, now in Shrek on Broadway) is desperate to escape accusations that he's either not black enough or is passing for black much the way he's passing for sensitive or profound. One would think Lee would find all sorts of magic in probing and presenting how the Youth transforms into the cynically realistic Narrator (Stew), even uncovering depths on film that were harder to find onstage.

To an extent that's true, although it's for reasons more related to the medium than the mediator. The stage show, for its many virtues of production, was just short of ear-splittingly loud, which often made it difficult to absorb the deeper nuances of the lines and lyrics. The film can't help but be quieter and more personal, resulting in crisper and clearer dialogue and lyrics that emphasize the work's oral elements without instilling aural pain.

There is a tradeoff, however, and a big one: Stripped of his ability to conceive the work from the deck up, Lee evinces far too much difficulty working within the strictures of the stage artists' visions. You lose the epic panoramas of emotional exclusion that the show's director, Annie Dorsen, constructed on the smallish stage of the Belasco Theatre. By extension, dozens of barely perceptible visual jokes (often in the minute ways the cast interacts with the onstage band and with each other) and the few major scenic effects (such as the revelation of David Korins and Kevin Adams's stunning light wall backdrop) are either lost altogether or made into afterthoughts. Karole Armitage's choreography looks muddy and flustered, not at all like the bouts of orgiastic self-expression they embodied onstage. And because theatre staging has its own requirements and challenges, Lee must use far too many off-angle and jaggedly edited shots just to get all the necessary action and actors in the frame in the first place. You lose all sense of the show's brutally stark style and the pulsating energy, unmatched in any recent musical in my memory, that all these individual elements helped kindle. The documentary aspects, most visible in the few minutes of backstage intermission badinage, are not a sufficient substitute.

But if Lee's film doesn't capture the musical's raw, visceral appeal, it nonetheless makes a sterling case for the material itself. Passing Strange is not a clunkily conventional attempt to retrofit the "clichéd" Broadway musical with new-sound music, à la Spring Awakening (which opened about a year earlier). Stew, who worked on everything, and Rodewald, who helped with the music and plays and sings in the band, have created a dazzlingly complex work that fuses genres ranging from avant-garde cinema to burlesque minstrelsy to performance art to even show-tune standards into a biographical stream-of-consciousness concert. What starts as a battle between the disparate forces of the Narrator, pronouncing his life from a center-stage podium, and the reactionary Youth fighting his way through the relatively realistic domestic drama of his life, eventually shows how the two united into a single creative and psychological being.

It was never intended to be, and never could be, a traditionally told tale, and maintain the heartbreaking ironies of how Stew interacts with the Mother (Eisa Davis) he abandoned early on, or how the other women in his life (De'Adre Aziza and Rebecca Naomi Jones) continue to exist, long after having dissolved into his past, dancing themselves sick in the bass-heavy song cycle of his life. The dramatic and the diegetic blend so seamlessly that it's impossible to discern whether the full-cast nuclear first-act number "Keys," representing the Youth's romantic and sexual awakening, takes place in the past, present, or in both simultaneously. Like Cabaret and Chicago, Passing Strange draws its content from its concept, it doesn't just blithely hold it up and claim artistic street cred, as so many quote-unquote daring musicals today so frequently do.

Lee's film beautifully preserves all the outstanding performances. Breaker made a momentous musical debut here, smoothly transitioning from callow youngster to pained underdeveloped adult into Stew himself—watch how his hand gestures and vocal cadences so gradually that they require literally the movie's entire running time (about two hours and fifteen minutes) to complete. Davis is remarkable as well, fierce and funny in parodying both the stereotypical ghetto mom and a French art-house waif, but shattering as the Mother fighting as much against herself as her son, wrenching out an unvoiceable goodbye with a cascade of tears. Aziza and Jones are scorching as the Youth's round-robin romances, though Aziza's jazzier parts (a secretly slutty choir girl, an inventive post-modern pornographer) give her more latitude and the actress's more natural delivery style translates better to film than Jones's bulging-eyed intensity (which made her dynamic onstage). Colman Domingo and Chad Goodridge are a hoot as the male chorus; Domingo, especially, eats up the screen as both a pastor's pot-smoking son and a post-modern German cabaret artist whose act looks far weirder and scarier-funnier on film than it did in the theater.

Stew has a bit more trouble. Though a consummate concert artist whose magnetically underplayed style anchored the show onstage, he more than anyone else is a victim of Lee's overactive closeups. Lee cuts to him so often, and at such close range, you can get very little sense of the scope of the show occurring just beyond the boundaries of his face.

What Lee apparently misunderstood is that though the show tells Stew's story, the Narrator is the vehicle, not the subject. Although those who saw the show will undoubtedly be able to "see around" this to recognize this film as the vital document it is of a groundbreaking musical, those who missed it live may have trouble understanding exactly what the fuss was about. The Youth comes to believe that "Life is a mistake that only art can correct," but without a broader view of the life in which they're all contained, Lee's art does Passing Strange more wrong than right.

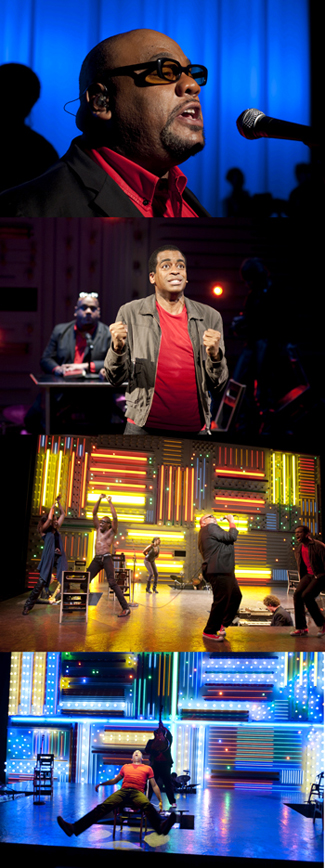

Photos by David Lee. From top to bottom: Stew; Daniel Breaker; the company of Passing Strange.

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Matthew Murray, click the links below!

Previous: Reviewing the Tony Situation

Next: The Urge to Emerge

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman