[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

Make Friends with the Truth by Matthew Murray

-

It's always sad to see a musical close when it has a first-rate pedigree, a top-notch creative team, and a wonderful score. Shouldn't that be enough to keep any show running for at least a season? No, it shouldn't. That's why, disappointed as I may be on some level, I'm shedding no tears for The Scottsboro Boys, which will close on Sunday after a Broadway run of only 49 performances. Despite what there is to admire about this most recent (and perhaps final?) John Kander and Fred Ebb musical, this is the outcome the show was gunning for from the beginning—whether Kander, Ebb, librettist David Thompson, director-choreographer Susan Stroman, and its many fervent admirers knew it or not.

It's always sad to see a musical close when it has a first-rate pedigree, a top-notch creative team, and a wonderful score. Shouldn't that be enough to keep any show running for at least a season? No, it shouldn't. That's why, disappointed as I may be on some level, I'm shedding no tears for The Scottsboro Boys, which will close on Sunday after a Broadway run of only 49 performances. Despite what there is to admire about this most recent (and perhaps final?) John Kander and Fred Ebb musical, this is the outcome the show was gunning for from the beginning—whether Kander, Ebb, librettist David Thompson, director-choreographer Susan Stroman, and its many fervent admirers knew it or not.To understand why, you must examine the trajectories of both Kander and Ebb's own amazing career, and of the genre of the concept musical, which the team ushered in with their Cabaret in 1966. Cabaret was not the first concept musical; I would argue that was Rodgers and Hammerstein's Allegro in 1947 or, if you don't consider that a true concept musical (which, given its structure, is fair), Alan Jay Lerner and Kurt Weill's Love Life in 1948 (about which there's more to say presently). Cabaret, however, was the first one that hit, happening upon the proper combination of source material, creative vision, and audience willingness needed to succeed. There's no question that it's a visionary work, explaining the collapse of Germany's Weimar Republic and the growth of Nazism using a seedy nightclub as a frame. The club, its Emcee, and even its house band evolved over the evening to generally demonstrate how decadence could become despair and how despair could become destitution, while the two-pronged central story (about an American writer romancing an English singer and a German woman romancing a Jew) echoed the same idea in more specific ways. The concept and the story didn't just need each other, but each made the other more than it could have been alone.

The same was true of the Kander–Ebb–Bob Fosse Chicago (1975), which envisioned vaudeville as the ultimate expression of common sense's sacrifice on the altar of entertainment. Anything could be sold and spun to an unwitting public if the press only cares about is selling papers, and their readers only care about show business. So two women whose greatest claims to fame involve murdering their lovers, are able to rise to the highest echelons of popular stardom using the public's own slavering indifference as a stepladder. The vaudeville turns that constituted the score highlighted this, showing how everyone—if given a chance—will sell out himself or herself for applause; that they mimicked 1920s-era stars like Bert Williams and Sophie Tucker was, if not coincidental, at least incidental to the greater point being made.

From then on, Kander and Ebb treated the entertainment world a bit more around the periphery, though it still informed nearly every one of their shows: The Act, Woman of the Year, The Rink, Steel Pier, Curtains, and All About Us. It only played a central thematic role again in Kiss of the Spider Woman (1993), in which a despondent inmate conjured up memories of a famed musical-movie actress to maintain his sanity across years of imprisonment. Even The Visit, a largely faithful adaptation of the 1958 Friedrich Dürrenmatt play about the dangers of societal groupthink, contained some allusions to the allure of performing. For better or worse, Kander and Ebb just couldn't turn it off.

You can argue whether or not these injections worked, but I personally don't think they ever did any real harm until extremely late in Kander and Ebb's career. The burned-out world of The Visit had no room for the kinds of buoyant songs and dances Kander and Ebb shows had so long been full of, yet they were present anyway. It, at least, had the good sense to not use a conceptual frame to try to sell itself. No audience would have bought that story as being enacted, say, as an entertainment at Anton's funeral. Some stories simply need to be told straight.

The Scottsboro Boys failed because it did not recognize this—but only in part. Just as much of its doom can be traced to other poor decisions that don't deserve to be overlooked merely because of Kander and Ebb's storied history or the show's obvious good intentions. Could Broadway and its audiences have embraced the show more? Of course. But aspiring musical writers, producers, and even some audiences members could learn more—and do far more to improve the state of Broadway—by studying what it did wrong, and working to keep these mistakes from happening again in the future.

1. It didn't earn (or properly use) its concept. Two major miscalculations with The Scottsboro Boys link directly back to the writers' employing the framing device of a minstrel show to tell the tragic story of nine black men falsely accused of raping white women in Scottsboro, Alabama, in the early 1930s. First, unlike Cabaret and Chicago (and, to a lesser extent, Kiss of the Spider Woman, it didn't derive its strength from its method of telling a story—the one and only thing a concept musical must do. The frame allowed for a showy dance opening, three foundational minstrel-show characters (the Interlocutor, Mr. Tambo, and Mr. Bones) to play many of the chorus parts, and a way to justify a sparse design. But the minstrel show never felt like it belonged, and the conceit vanished for huge swaths of time to let the men's stories unfold as if legitimate, unprocessed action. In true concept musicals, the concept persists because it has to or the show falls apart. Were The Scottsboro Boys done straight, it would work at least as well, meaning the concept was excess—and should have been excised. The second misstep was in further undermining the concept by wrapping the minstrel show within a frame of its own: a black woman about to step into history herself, who imagines the Scottsboro boys' story into existence. It may be possible to weave two competing devices together in this way, but it must be justified far better than Kander, Ebb, and Thompson could manage—here it just felt like they had two ideas they were desperate to use, and didn't really care that they didn't work together. If the writers don't commit to and believe in what they're writing, why should anyone else?

2. It didn't justify its characters. The trouble with any ensemble show of any type is: How do you evenly distribute weight between characters (or actors) and still help the audience follow the action? Thompson's solution for The Scottsboro Boys was to focus on one of the accused men, Haywood Patterson, to the point that not only did the others become virtually anonymous, they were reduced to doubling (and tripling) to play roles in their own story—something only Tambo and Bones were established as doing in the opening number. You focus on Haywood not for any narrative reason, but because the writers need to particularize their subjects somehow, and how can you do that to nine people? I would argue that A Chorus Line did it with 17, and even if you want to argue that there only six or seven "major" roles, most of which are spiritually subservient to Cassie, that still represents a far richer array of characterizations than you get in The Scottsboro Boys. By making the story of these nine men so much the story of just one, the writers marginalized their subjects and alienated audiences from understanding the true, devastating scope of the injustice they wanted to present.

3. It was antiquated, in more ways than one. You don't need to have visited a Weimar nightclub to understand its function or importance in Cabaret, and Chicago didn't demand its audience have experienced vaudeville the first time around (though many of them surely did) because it explained just enough as it went along. Because The Scottsboro Boys never believes in its own concept (see number 1, above), it's harder for us to accept on faith what it tells us about a form of entertainment that was in its death throes 80 years ago when the show is set. Audiences can relate to nightclubs, films, and individual performers' acts (what else is American Idol?), but traditional minstrel shows have very little to do with our culture today. Love Life, which climaxed in a minstrel show and used vaudeville as its framing device throughout, did so because its passé nature was crucial to its story: to thrust Sam and Susan Cooper back to the more reasoned and sensible early years of their marriage. But its final scene was set in the real, then-contemporary world of 1948—The Scottsboro Boys ends in 1955. In the span of 45 years, Kander and Ebb had transitioned from speaking in the popular vernacular to speaking in a language very few alive today remember, and climaxing their action in a year that's still 55 years removed from our own. If Kander and Ebb were not writing for 2010 audiences, why should anyone expect 2010 audiences to respond with enthusiasm?

4. It didn't look good. I think audiences are willing to forgive a show an inexpensive design as long as it looks appropriate for what it's doing. Those familiar with the minstrel show form understand the importance of chairs to its presentation, but as a scenic device they lack potential and look cheap. For a real minstrel show, which is a fairly frivolous entertainment that makes little in the way of dramatic demands, it's not a problem. But it's difficult to accept chairs as things like trains, jail cells, and courtrooms—no matter what you do with them, they really only ever look like chairs, and forcing that upon the audience is drawing them out of the world of the story before they have a chance to become immersed in it. Yes, The Scottsboro Boys had a nice painted backdrop, but otherwise it was a lot of drab, basic colors laid out against walls of chairs that, painted a shiny silver, didn't even look like they belonged in the era they were assigned to create. Tommy Tune's Grand Hotel famously used chairs to a huge extent in outlining its world, but (a) used nearly 40 of them, (b) had a cast of 30, and (c) surrounded the chairs on three sides with a luxurious-looking hotel backdrop that only expanded on the chairs, none of which The Scottsboro Boys did on Broadway. You couldn't help but think the minstrel show conceit was selected specifically because those chairs could whittle down the set budget to almost nothing—and when that's where your mind is, again, it's not on the show.

5. It didn't get the attention it needed, even though it got the chance. For me, the saddest part of The Scottsboro Boys is that all of these points could have been addressed. The show opened Off-Broadway at the Vineyard Theatre earlier this year and had sell-out houses and reviews that, if not across-the-board raves, were certainly encouraging. But rather than moving to Broadway right away, it detoured through the Guthrie Theatre where, we were told, the creators were making changes to it to get it into spit-shined Broadway shape. When it opened at the Lyceum, one song had been cut, one scene had been rewritten to say the same thing in slightly different words, and a handful of other lines had received minor nips and tucks. Every structural problem, every dramatic failing, every piece that didn't add up—all of which had been pointed out by the critics before—was still in place, and the show looked just as it had Off-Broadway, even though it was on a wider and deeper stage that stretched the design's already-limited effectiveness beyond the breaking point. Whether this happened because there wasn't money to implement large-scale changes, because no one involved wanted to remove or rewrite the late Ebb's lyrics, or because the creators honestly believed their work was good enough, the fact remains that The Scottsboro Boys returned to New York every bit as flawed as it had been when it left. The show had had eight additional months and looked as though barely eight additional minutes had been spent on it. There was a time when entire, finished musicals were rethought, rewritten, redirected, rechoreographed, and sometimes even recast in just two or three weeks out of town. For The Scottsboro Boys to begin with the unassailable advantage of uniquely gifted and experienced writers, and then waste two-thirds of a year that could have been spent renovating it into perfection, is as dispiriting as today's musical theatre gets. Certainly Stroman, Kander, Thompson, and producers Barry and Fran Weissler didn't want The Scottsboro Boys to fail, but did they really try as hard as they could have to make it succeed?

The Scottsboro Boys has, at least, produced a cast recording that captures the score in all its considerable glory, and will forever let interested listeners hear what definitely ranks as one of Kander and Ebb's finest compositions. It's even being rumored that the Weisslers will bring the show back in the spring so Tony voters don't forget how good the songs and Stroman's staging and choreography were—these are awards it has a real and deserved chance of winning. The recording and this temporary resuscitation are sure to inspire theatre companies all over the country to take on the show themselves—everyone who laments the quick closing of The Scottsboro Boys this time around may at least find some solace in the fact that we have not even remotely heard the end of it. In truth, the overture of its life probably hasn't even wrapped up yet. As it always does, posterity will take care of itself, and there's much in The Scottsboro Boys it would do well to embrace. But it helps nothing and no one to pretend the show is better than it actually is, when a balanced accounting of its virtues and stumbles alike would be much more apt to keep this kind of musical theatre tragedy from ever happening again.

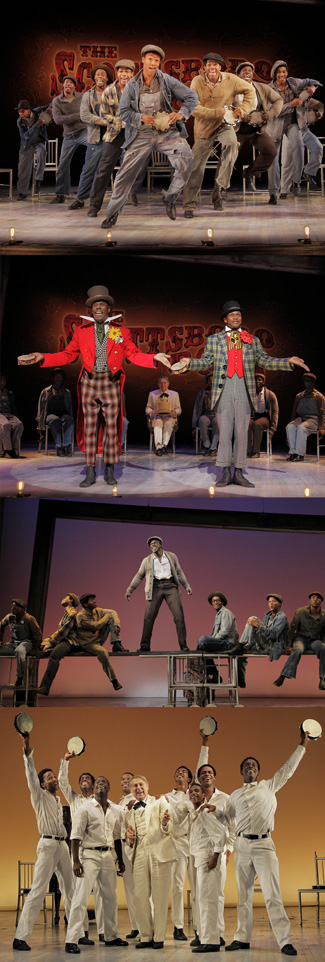

Photos of The Scottsboro Boys on Broadway by Paul Kolnik. Top to bottom: The cast; Colman Domingo and Forrest McClendon; Joshua Henry (center) and company; John Cullum (center) and company.

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Matthew Murray, click the links below!

Previous: Think Big, but Also Think Smart

Next: Theatre History 101

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman