[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

Follow Spot

by Michael Portantiere

You Go, Girl!

-

When the very title of an opera sets some people to giggling, and the opera is not a comedy, that's quite a hump to get over in terms of audience acceptance. When the name of the primo tenore character in the same opera pairs two slang terms for "penis," that's an even bigger hump. Giacomo Puccin's La Fanciulla del West certainly has a few moments of unintentional humor. But in much the same way that its hero, the bandit Ramerrez (alias "Dick Johnson"), is redeemed by the love of a good woman, the work itself is ennobled by its ravishing melodies, its brilliant orchestrations, and Puccini's unerring skill as a musical dramatist.

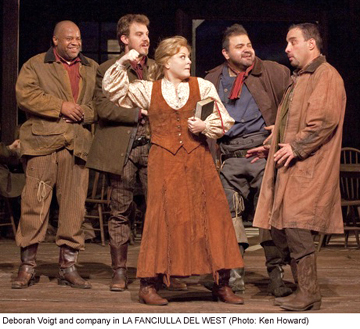

Fanciulla turns 100 years young this coming Friday, having premiered at the Metropolitan Opera on December 10, 1910, and the centenary is causing a flurry of renewed interest. The San Francisco Opera just recently revived the work with the great Deborah Voigt starring, and now the Met has brought back its excellent Giancarlo del Monaco production, this time with Voigt, Marcello Giordani, and Lucio Gallo in the leads.

Based on the play The Girl of the Golden West by theater impresario David Belasco, whose Madame Butterfly had previously inspired Puccini, Fanciulla was a daring endeavor on the composer's part -- perhaps most daring of all in that it premiered in America, at the Met, rather than in Italy. (Can you imagine the reception Rodgers and Hammerstein's The King and I might have received if it had opened in Thailand?) Fanciulla was a boffo box-office success at the Met in 1910, but that was due in no small part to its starry lead cast (Emmy Destinn, Enrico Caruso, Pasquale Amato), its proto-legendary conductor (Arturo Toscanini), and a knock-your-socks-off production supervised by Belasco himself. The reviews of the work itself were mixed, to put it mildly.

The opera is often cited half-jokingly as the world's first Spaghetti Western, having been written more than half a century before the name Sergio Leone meant anything to anyone. The setting is a mining camp in California circa 1849-50, at the height of the Gold Rush. We're introduced to life at the Polka saloon, owned by a gal named Minnie, who serves as a combination mother/sister/schoolmarm/crush for the miners. Our heroine is pursued by the local sheriff, Jack Rance -- but he's married, so she's not interested. Besides, she finds herself falling in love with Dick Johnson, a stranger who has just come to town and who eventually turns out to be the notorious bandit Ramerrez. When Minnie discovers his true identify, she's horrified at first, but then she has a change of heart. Just as the men prepare to hang Johnson in the forest, Minnie arrives on horseback and talks them out of it, claiming him as her own. They walk off into the California sunrise together, presumably to live happily ever after.

Though Fanciulla got off to a bang-up start at the Met, revivals have been relatively few and far between. One possible reason is the incongruity of all them rough-hewn, forty-niner-miners knockin' around in an Italian opera. This construct has always presented a special challenge for American audiences; some folks who aren't bothered in the least by the suggestion of Spanish, Egyptian, and Japanese music and culture in Bizet's Carmen, Verdi's Aida, and Puccini's own Madama Butterfly have trouble accepting the characters in Fanciulla singing "doo-dah, doo-dah-day," referring to "Soledad" and "Wells-Fargo," and letting out with shouts of "hello!" and "wiskey!"

But there's another reason why the opera is still something of a rarity: The roles of Minnie and Johnson are extremely challenging to sing. In 1961, Leontyne Price experienced a rare debacle when she lost her voice in the middle of a Met performance of Fanciulla and Dorothy Kirsten had to step in -- or, rather, ride on -- to sing the third act. At New York City Opera in the 1980s, a tenor who will remain nameless was unable to deal with the climactic phrase of Johnson's Act II aria "Or son sei mesi" one evening and ended up shouting rather than singing the notes. Although Renata Tebaldi made a much-admired recording of the opera in 1958, she didn't tackle the role on stage until she tried it at the Met in 1970, at the tail end of her career -- and, according to one longtime fan who attended, she did "a lot of screaming."

Despite its difficulties, Fanciulla will always be with us because it plays like gangbusters, and because the music is so gorgeous. Though Puccini was Italian to the core, he endowed the opera with a credibly Wild Western sound -- so much so that this work, rather than Rossini's William Tell, might as well have been raided to provide the theme music for the old-time radio and early TV series The Lone Ranger. Of course, Rossini's music had already fallen into the public domain by then, whereas Puccini was still under copyright.

While we're on that subject: According to some reports, Andrew Lloyd Webber was sued by the Puccini estate for appropriating a melody from Fanciulla for use in The Phantom of the Opera, and settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. The tune in question is first heard during the brief, tender dance between Minnie and Johnson in Act I of the opera and, not long thereafter, is sung full out in Johnson's arioso "Quello che tacete." Listen to the lovely, yearning melody that accompanies the words "e provai una gioia strana," and if you think it sounds an awful lot like the "silently the senses abandon their defenses" section of "Music of the Night" from Phantom, you're not alone.

Considering that Fanciulla was composed 100 years ago and is set in a Wild West far more mythical than historical, it's not surprising that much of the opera strikes 21st century audiences as quaint. Some of the plot devices inherited from Belasco are enough to make us groan or, at least, smile in superiority. One of the supporting roles, the minstrel Jake Wallace, was originally intended to be played in blackface (though this never happens in modern stagings), and the opera's two Native American characters, Wowkle and Billy, are written in a way that rankles present-day sensibilities. (Librettists Guelfo Civinini and Carlo Zangarini actually have them exclaim "Ugh!" on several occasions, another holdover from Belasco.)

Yet there are many poignant moments in the opera, most notably the hushed ending of Act I and the stunning Act III scene in which Minnie pleads for Johnson's life. There are also some passages of real wit, as in an early exchange between Minnie and the Polka's bartender in reference to the newly arrived Johnson. (NICK: There's a stranger outside. MINNIE: Who is it? NICK: I've never seen him before. Seems like he's from San Francisco; he ordered whiskey and water. MINNIE: Whiskey and water? What sort of concoction is that? NICK: That's what I said. "At the Polka, we drink our whiskey straight." MINNIE: Well, let him come in. We'll curl his hair for him!)

If many commentators in 1910 underrated Fanciulla, its composer did not. On the contrary, Puccini declared it to be "my strongest opera, and the most full of color, the most picturesque, particularly in orchestration." As we see Minnie and her beloved go off to begin a new life at the end of the opera, we can only be grateful that Puccini chose to apply his genius to this perishable melodrama of the Wild West and turn it into something immortal. Be sure to catch it at the Met, where it first came to life 100 years ago this week. For more information, click here.

Published on Saturday, December 4, 2010

Michael Portantiere has more than 30 years' experience as an editor and writer for TheaterMania.com, InTHEATER magazine, and BACK STAGE. He has interviewed theater notables for NPR.org, PLAYBILL, STAGEBILL, and OPERA NEWS, and has written notes for several cast albums. Michael is co-author of FORBIDDEN BROADWAY: BEHIND THE MYLAR CURTAIN, published in 2008 by Hal Leonard/Applause. Additionally, he is a professional photographer whose pictures have been published by THE NEW YORK TIMES, the DAILY NEWS, and several major websites. (Visit www.followspotphoto.com for more information.) He can be reached at [email protected]

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Michael Portantiere, click the links below!

Previous: The Extraordinary Ordinary

Next: The Gypsy in Carol Channing's Soul

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman